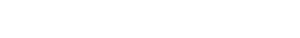

Memoirs of A Student:

Maria Menjivar

By Bill Howard

In the dark days of the bloody civil war in El Salvador, Maria Menjivar found sanctuary away from home at Santa Luisa School. The war — which heated up in the late 1970s, erupted in 1980 with the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero and ended in 1992 — claimed the lives of an estimated 75,000 people, with tens of thousands of people also declared missing. During that time, it was common for schools to be raided by armies on both sides. Boys would be conscripted into the visiting army and girls would sometimes be kidnapped and possibly raped and murdered. When Santa Luisa was targeted, the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul who ran the school would funnel the students to a hiding place at a nearby church and keep watch until the soldiers left.

Maria now thrives as an accountant in Maryland, but her heart still has fond memories of her time as a student at Santa Luisa. In addition to finding refuge there from the street violence, Santa Luisa shielded Menjivar from a culture of drug and alcohol use that was easy to fall into. Santa Luisa served as a place of stability for her when her parents were going through a divorce. Santa Luisa was where Maria was educated in the Catholic faith. “I’m thankful I went there,” she said.

Memories of a Solid Catholic Foundation

“Santa Luisa was very Catholic. The values were there,” Maria said. “The nuns were very strict and very good teachers.” From 1977 until 1982, Maria attended grades 1-6 at Santa Luisa. Admission to Santa Luisa was highly competitive, she remembered, with a quality education offered for just a few dollars a year. “The number of people who wanted to take their kids there was high. The monthly fee was really small and your kids still got the education of a private school,” she said. The school day always began with the students lining up for prayer and for a uniform check. Each grade would head out to a long patio that ran along the school building. The nuns would hand out a prayer that the students would say and then each class will file into their respective classrooms.

Classes would start at 7:30 a.m. and go until a half-hour lunch break around 12:30 p.m. The nuns had a strict uniform code, which made recess a particular challenge in keeping their white shirts clean. Students would stand up and greet the teacher when she entered the classroom. Religion classes were part of the everyday curriculum. Gym classes were held twice a week. All tests were handwritten – both questions and answers – leaving less time to provide answers. While the names mostly escape her now, Maria remembers one lay teacher, Julia, who provided in her the math foundation that would eventually lead her to become a successful accountant. “You have to know the basics and I had such a good instructor,” she said, adding that she had learned her tables by second grade.

The nuns were demanding and Maria particularly remembers the pressure students faced in passing their first Communion tests between third and fourth grade. Homework assignments were sometimes tied into the priest’s Sunday Mass homily, so students rarely skipped out on Sunday Mass. Maria said the curriculum “helped us to help each other bond with values and to follow the commandments. It helped me a lot overall, because I was able to keep my faith in knowing the things I shouldn’t do.” Honoring parents and one’s peers was a big part of life at Santa Luisa, and Maria fondly remembers how the nuns would lead the students in special events to celebrate Mother’s Day, Father’s Day and Teacher’s Day. “Each grade would do a dance or a show. Mother’s Day and Father’s Day were huge. We’d have a big dance with Salvadoran music and we’d dress up,” she said.

A quiet student, Maria didn’t get into trouble and was, in fact, respected highly by her classmates. For second, third and fourth grades, she was voted the president of her class. “I had to set an example,” she said. Students would stay with one teacher from first grade through sixth, she said. From there, the boys would move on to another middle school and the girls would remain but have different teachers for different subjects. When Maria attended Santa Luisa, the school was actually split in half, with one building for boys in grades 1-6 and the other for girls in grades 1-9 (the school is now co-ed). Maria recalled a subdivision that separated the two schools, with a large, wooden door providing access between them. She also remembered another special door – one that led to a passageway from the school to the Church of St. Paul around the corner.

“Because there were fires and guns and shooting, to keep us safe the nuns would take us so none of the shooting would hit us through the walls,” Maria said. Although the civil war stole part of her innocence, Maria said Santa Luisa still protected her in other areas and helped her develop strong senses of discipline and responsibility. “I never saw drugs there, so I never discovered them or got into that trouble,” she said. “There were things that they taught me not do. I couldn’t imagine skipping classes.” When rumors of imminent fighting would circulate, the nuns would often send the students home while the roads were still safe. But sometimes the fighting came unannounced. “When the war first started, there was a lot of fighting around the neighborhood. I couldn’t leave the school without my brother,” she recalled. Maria’s brother was one of the fortunate boys spared ensnarement by one of the armies.

At the time, jobs were nearly impossible to find in El Salvador, a tension that played a large part in her parents divorcing. Maria’s mother emigrated to the United States in 1978, but because she wasn’t earning a high-enough income in her new job, she was unable to bring her two children with her. The income was enough to keep sending Maria and her brother to Santa Luisa, and they stayed behind with their grandmother and other relatives on their mother’s side. Maria didn’t understand at the time that her mother would be gone for such a long time, but when the reality began to hit her, the Santa Luisa community was there for her. “My teacher did know about it and they were a great help understanding what we were going through,” Maria remembered.

Long Since - But Never Completely - Gone

Nearly three decades later, the civil war has ended but the tension between the haves and have-nots remains. Most of the Connecticut-sized country is owned by a small, wealthy part of the population, leading many to live in practical slavery or risk their lives crossing the borders into more prosperous countries. About 25 percent of the country’s gross national product comes from monies sent back from laborers in the United States.

Almost eight years after her mother arrived in Maryland, Maria and her brother made the permanent move there. Maria arrived in November 1986 and enrolled at a community college to take classes to become a senior tax accountant. Maria eventually transferred to the University of Maryland, where she earned her accounting degree. She became a U.S. citizen in 1992 and lives in Maryland to this day. Maria’s brother would eventually join an army – the U.S. Army – so he could get a college education.

While surfing the Internet one night in the spring of 2007, Maria Googled the school name to see if it still exists. She was inspired to search in part because a friend had a sister who belonged to the Sisters of Charity. Maria’s search brought up the SCOPE Foundation, and she browsed through the site. She decided to make a donation to SCOPE’s mission of providing monetary, spiritual and technological assistance to help Santa Luisa keep its doors open to form its students in Catholic values. After asking to be put on SCOPE’s mailing list, an e-mail exchange ensued with SCOPE president Matthew O’Rourke where she disclosed that she had attended Santa Luisa.

“I looked at the pictures on the (SCOPE) Web site and couldn’t recognize the school because it changed a lot,” she said. The doorways were narrower when she attended, but the common patio has survived. Maria remembers the school grounds as more open and less busier, as the surrounding market has grown larger and crowds the school now.

The outside of the school may have changed, but Santa Luisa’s mission of the Catholic Church to form children in Gospel values remains a beacon in the community. Santa Luisa still shields its students from a culture of drug and alcohol use. Santa Luisa still serves as a place of stability for children in broken families and neighborhoods with crushing poverty. And Santa Luisa is where children receive a strong education and an essential formation in the Catholic faith. Like Maria Menjivar’s days there three decades ago . . . Santa Luisa still provides hope.

Bill Howard is an award-winning Catholic journalist and a SCOPE board member.